New rapid test uses viruses to identify the cause of bladder infections

Urinary tract infections are not only painful, unpleasant, and potentially hazardous but also present a considerable challenge for physicians. They're difficult to diagnose quickly, and conventional diagnostic typically methods take several days. These are several days in which the doctor usually prescribes a treatment, without being sure whether or not it will actually be effective.

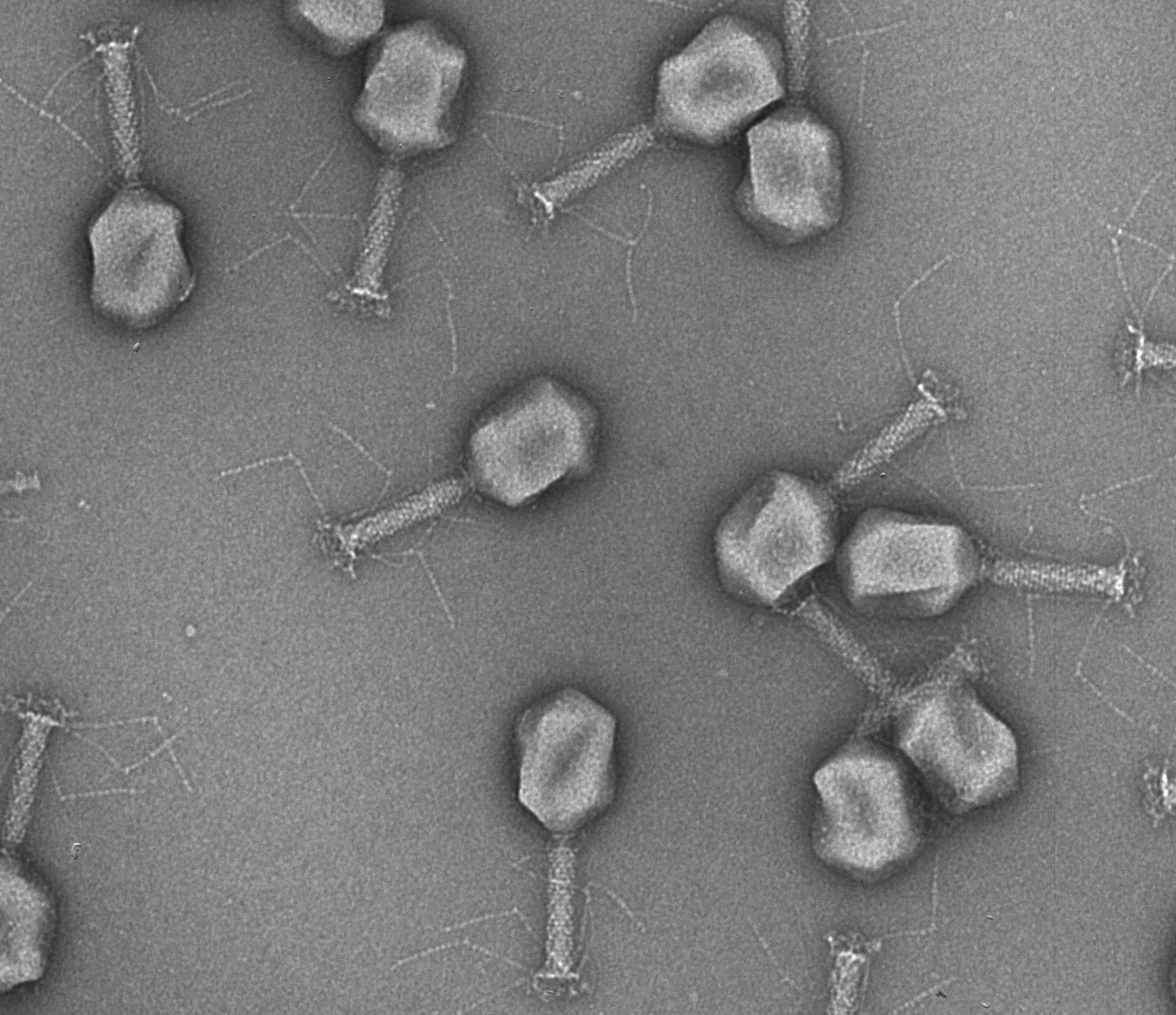

A team of researchers at ETH Zurich wanted to have a better diagnostic tool. In partnership with Balgrist University Hospital, they have developed a rapid test that uses bacteriophages -- viruses that infect bacteria -- to identify the pathogens that cause the infection. The team genetically modified the phages to make them more efficient to target bacteria.

Each type of phage targets only one particular type or strain of bacteria. The researchers led by Martin Loessner are now taking advantage of this characteristic with their new rapid test.

Better testing for bladder infections

Initially, the researchers focused on identifying phages capable of effectively targeting the three primary bacteria responsible for urinary tract infections: Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and Enterococci. These natural phages then underwent modifications to prompt any bacteria they infect to generate a readily detectable light signal.

This method enabled the researchers to reliably detect the pathogenic bacteria from a urine sample in less than four hours – instead of the several days of conventional methods. It's still early days, but once further refined, the approach could enable the researchers to prescribe antibiotics right after diagnosis.

But it doesn’t end there. This method also allows doctors to predict which patients are likely to respond well to tailored phage therapy. This is because the strength of the light signal produced during the assay shows how efficient the phages are in attacking bacteria. The stronger the glow, the better the bacterium will respond to the therapy -- so clinicians can prescribe the most effective treatment from the get go.

Phage therapies go way back but were largely left behind in Western countries with the discovery of penicillin. However, as antibiotic resistance increases, they are increasingly becoming a subject of interest. They also have the important advantage of going after one single bacterium, instead of trying to cover a wide spectrum, as many antibiotics do.

However, previous approaches had one problem. “Phages aren’t interested in completely killing their host, the pathogenic bacterium,” Samuel Kilcher, a study author, said in a statement. To address this, the team genetically modified the phages. These can now produce new phages in the infected host and their own antibiotics.

“There are also many academic and commercial clinical trials underway worldwide that are systematically investigating the potential of natural and genetically optimized phages,” Matthew Dunne, study author, said in a statement. However, there’s a long way before this happens, as extensive clinical studies still need to be carried out.

While this was only a proof of concept for now, the team will now test its efficacy in a clinical trial with a group of selected patients.

The findings were published in this study and in this one, both in the journal Nature Communications.